I Imagine My Family Singing Together

June 15, 2025

Fred Won’t Move Out trailer

My family when I was growing up lived on a dirt road in Katonah, a small town outside of New York City. Around a quarter mile from where we lived, the dirt road runs alongside a reservoir. The entire town of Katonah was moved in 1897 to accommodate the expansion of the water system for New York City. Today beneath the water of the reservoir are the foundations of the old town.

In 2009, my mother and I were taking a walk together, headed towards the reservoir, when she started to explain to me her interpretation of what seemed to me a random event of no particular importance but seemed to worry her. The object of her concern was an approaching car. Cars are rare on the dirt road but we did have neighbors and fishing is permitted on the reservoir. She explained that she thought the driver was intentionally driving towards her. The car continued driving past us. A few months later, she told us at Christmas that she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's. At first, I doubted this could be the case. Her own mother had retained an extraordinary memory at the end of her life, including after she had suffered a stroke.

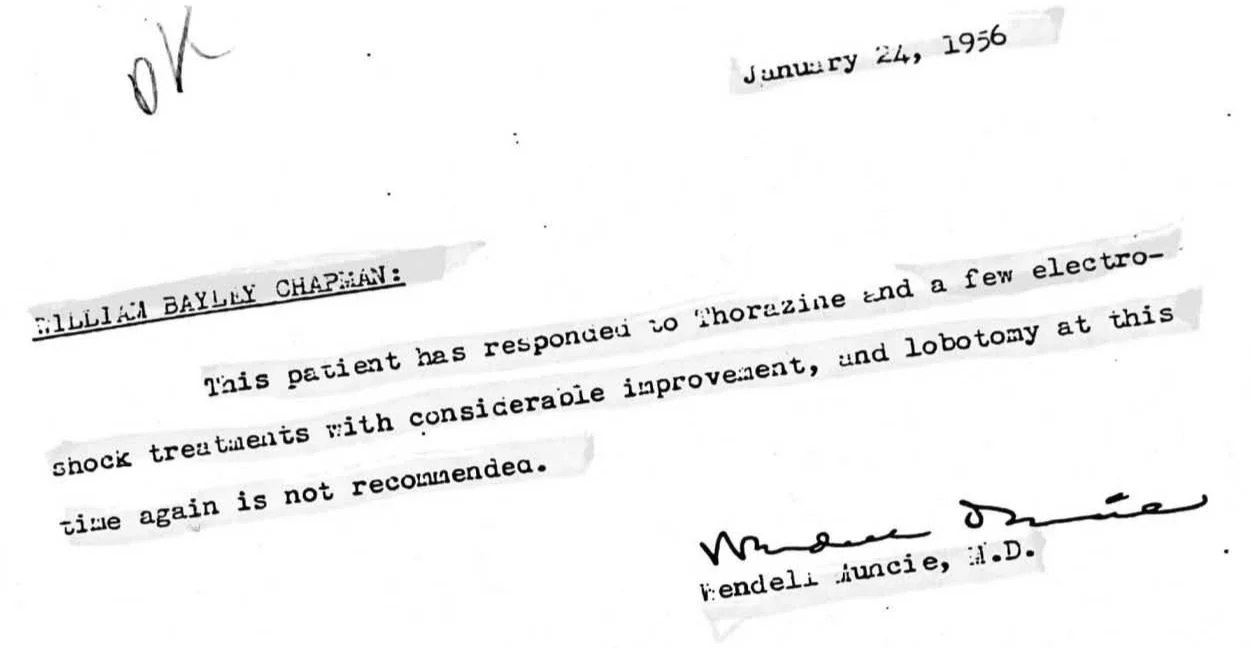

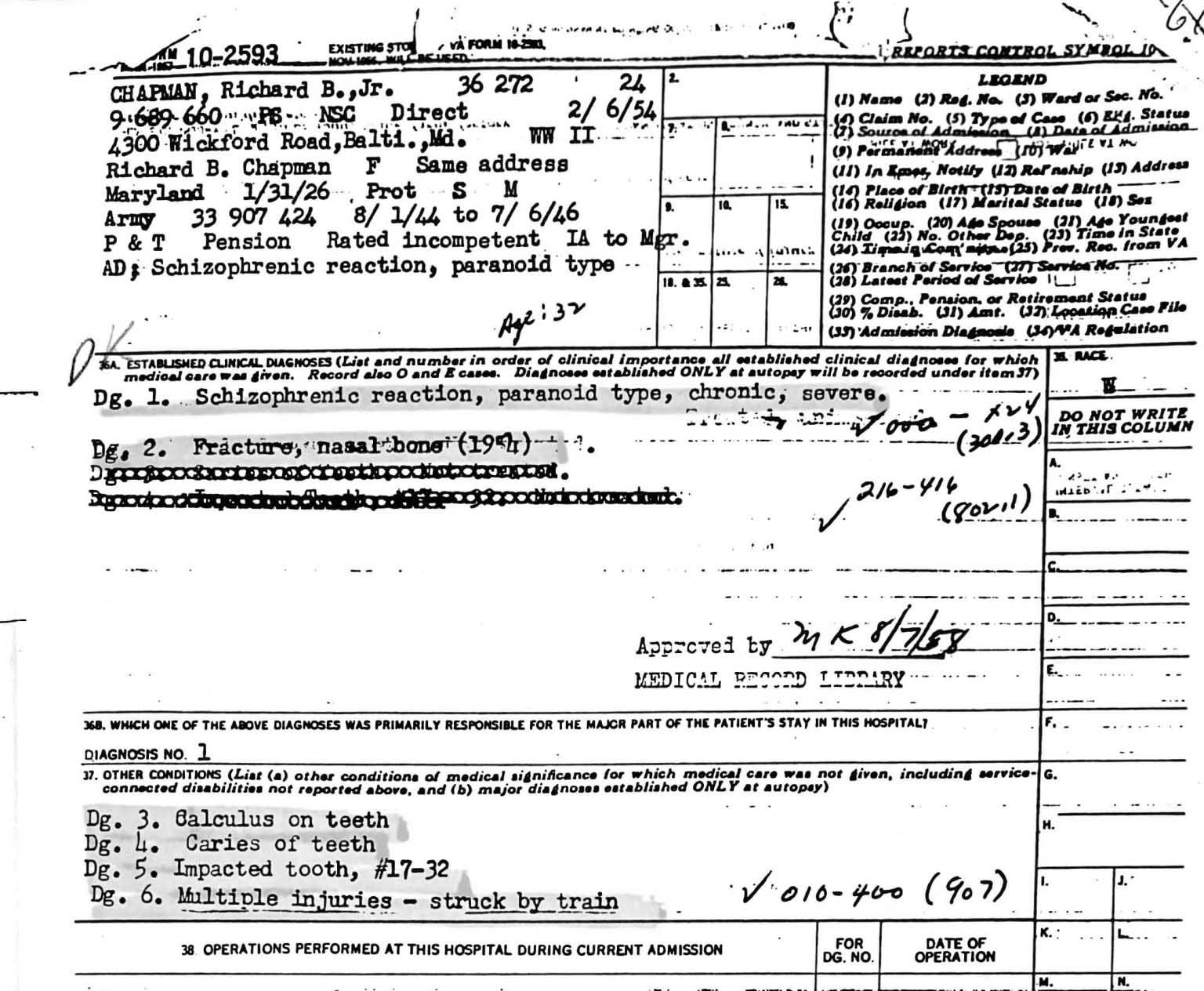

From my mother I once learned——I don’t remember at what time——that when I was a small child and my brother an infant, she had been persuaded by her mother not to attend her brother Richard’s funeral. What I didn’t know until I uncovered it in my late 30s was that her brother had spent the last ten years of his life being treated for schizophrenia in a veterans’ psychiatric hospital. This ended when he either intentionally or accidentally left the grounds of the psychiatric hospital and was hit by a train. His records show he had been considered a candidate for a lobotomy. In January of the year I was born——I was born in November, making three Richards in my mother's life for what would turn out to be a very short time——the psychiatrist in charge wrote: "This patient has responded to Thorazine and a few electroshock treatments with considerable improvement, and lobotomy at this time again is not recommended." The word that stands out for me is "again."

“Again.”

In my 20s, many years before my mother’s death, while my family was living in the same house on the dirt road that led to a reservoir, learning that my grandmother had suffered a stroke, I had made plans to drive down to Baltimore to visit my grandmother in a hospital. When I told my mother of my plans, she warned me that my grandmother would be unable to communicate and that she would be unaware that I was even in the same room with her. My mother further warned me that seeing my grandmother in such a state could be detrimental to my health. I connect my mother’s reaction to her own mother’s final illness to my mother’s memory of having once been advised by her mother not to attend her brother’s funeral. On one occasion my mother broke down in tears and told me about visiting her brother in the hospital with her mother. She said through her tears that her mother had only been able to speak about social events in Baltimore. My mother’s family, like my own family when we were children, was in the Baltimore Social Register, which has nothing to do with socialism.

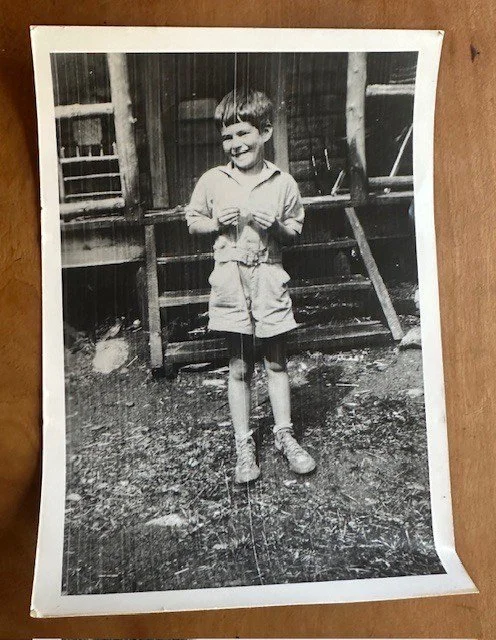

My mother’s brother Richard during a summer in Canada.

My mother felt her brother had been abandoned in the psychiatric hospital. The train that hit and killed him had been traveling towards Baltimore. One time she told me she thought he had been trying to get home.

teeth, teeth, tooth, struck by train

Knowing my grandmother had a love of poetry, I ignored my mother’s warning and drove to Baltimore with the Oxford Book of English Verse in the death seat. As I opened the anthology in the sterile hospital room, I could see half of my grandmother’s face was frozen like a mask. I remember the feel of the delicate paper as I leafed through the pages and found a poem I thought she might know. Her life story had been complicated before her only son’s death by the premature death of her first husband in a car accident. After his death, she had married Richard Chapman, my grandfather. The first Richard Chapman would eventually die of heart failure less than six months after the death of the second Richard, his son.

In the hospital room, I began to read Shakespeare’s sonnet that begins, “When in Disgrace with Fortune and Men’s Eyes.” She began to make noises with her throat. I realized that—despite her voice being distorted by the effect of the stroke—she was reciting the sonnet aloud with me. Our voices together reciting that sonnet by Shakespeare had a feeling of what I can only describe as a revelation—a word I also use to describe my feeling when I read the psychiatric records of her son who was my mother’s brother. After my mother died, I would have this experience again during the filming of Fred Won’t Move Out, shouldering the second camera in a scene in which the members of the family in the fictional film sing together. As a filmmaker I know how to manufacture a feeling of revelation. I distrust it. Yet there are times when a revelation persists through rereading and, for me, this has been true of these three moments.

After that last Christmas lunch in the dining room which would soon become her bedroom, when she could no longer take the stairs to the second floor, my mother looked incredulous as she told us she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's. I too was incredulous. However it soon became clear that my mother was—in a different sense of the term than I had previously considered—losing her mind.

The catalyst for my writing and directing Fred Won’t Move Out, my fourth film, was the possibility of filming in the house where my family had lived for over thirty years. My mother’s deteriorating mental and physical condition from Alzheimer’s and my father’s increasing lack of mobility and mental clarity had led them and our family to make plans for them to move into the neighborhood in the city where I and one of my sisters were raising our families. This is when the possibility of filming in the house had occurred to me. Also, my ability to make films was deteriorating in many ways. I too needed to make a move. Largely improvised, the film Fred Won’t Move Out became a leap into the unknown that proved salvational for me as a filmmaker and for my sense of how filmmaking was integral to my life as an artist.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

Fred Won’t Move Out gave me an opportunity to go farther in the direction of improvisation than I had done previously. From the start of conceiving of it as a fiction film, I felt I would be sustained by my intimate connection to the story, to the characters and also to the location. The first performer I asked to be in it was Elliott Gould, with whom I had previously worked in my second film, The Caller. Of Elliott Gould’s performance in Fred Won’t Move Out, the British Film Institute (BFI) would eventually name it one of his ten best performances.

While filming one day during The Caller, I had asked Elliot Gould and Frank Langella, with whom he was co-starring, to improvise a few lines of dialogue in order to get us out of a scene. Gould does this like a distinguished jazz musician. Listening to Gould improvise triggered a desire inside me of which Fred Won’t Move Out would be the realization.

I knew Elliott Gould’s work mainly through his acting in the films of Robert Altman. Altman is a filmmaker of the greatest importance for me. Not only because of his work but because a former professor of mine, Helene Keyssar, had been writing a book on him at the same time that I was studying theater with her. There was no film program then at the college I was attending and she was an exceptional source of encouragement for me and my work. Also, before the days of readily available VHS tapes——she and her husband, the philosopher Tracey Strong, would screen 35 millimeter prints of films in their living room̉——including those by Altman. Altman was known for his use of improvisation and Gould’s extraordinary performances, particularly in The Long Goodbye, had made him an actor for whom I have the greatest admiration and respect.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

With Fred Won’t Move Out I wanted to work quickly. I wasn’t certain how long I would have the house and because elements of the story and the place where we were filming were so deeply engrained in my memory, and because Elliot Gould had said yes, I was confident that I wanted to work in this way.

I had been away at private schools most of my education and envied my siblings who had stayed home for most of theirs. This meant that I had a certain nostalgia and had carefully studied how the sun rising and setting illuminated the walls and the antique American furniture my mother had inherited and brought from Baltimore. I remember climbing in the trees that surrounded the house and contemplating the lives of its occupants, consisting of my family, the people who worked there and the other people who passed through it. I was mesmerized by the prospect of filming here. This was the film I could make with my eyes closed, and I realized I needed to close them if I wanted to find my way forward as a filmmaker.

We shot sequentially, filming the scenes of the story in the order in which the film would be assembled. I knew Altman was one of the very few directors who insisted on working this way. Filming in the order in which the story will eventually appear on the screen has great advantages for the cast and for the crew. Film productions are usually obliged to shoot in an order largely dictated by the budget and the distance between locations. Filming in the order of the story usually would be considered an indulgent luxury. In such a case, an actor, for example, cannot spontaneously give her character a trait in the first scene when she knows she has already shot later scenes in which this trait of her character would have to be present. Shooting sequentially allows us——cast and crew——to improvise as we go along. It frees us to include new ideas about the characters and ways of filming as they develop that would otherwise have to be excluded. While this way of working is usually ruled out by issues of cost, for a few filmmakers——including two of the most important for me, Robert Altman and Michelangelo Antonioni——this has been a line in the sand, a deal-breaker. Because Fred Won’t Move Out would be filmed entirely in one location, in the house where my family had spent the majority of their time while I was growing up, I was able to film in the order in which the story unfolds.

We planned to shoot over three weeks. Each Sunday before the following week’s filming I would send out a draft of the breakdown of scenes and dialogue for the coming week to the actors and crew. I let them know that I might choose to improvise additional scenes at the last moment.

Also as a consequence of how we were working——not knowing what scenes would be added for the following week——all the actors were required to be present as much as possible over the entire three weeks. This strengthened the sense of community between the cast and main members of the crew.

One very interesting character in the film is a music therapist. Altman had been known to cast non-professionals in the roles they played in their actual lives and this influenced me to ask the film’s composer and musical consultant, Robert Miller, if he would play the role in the film of a music therapist. On my film The Caller, to which his great score had contributed immeasurably, I had seen Robert, when working with actors, exhibit skills that I thought would make him credible as a music therapist working with a family, one of whose members has Alzheimer's.

The crew was led by Valentina Cangilia as the director of photography. From Naples, Italy, Caniglia and I have so far collaborated on four feature films, most recently Adieu Lacan. Working with her on this film introduced me to one of my most gifted and persistent collaborators. I was determined to work with the Canon 5D, a prosumer camera that was popular with low-budget filmmakers at the time. I also occasionally wanted to operate a second camera. She was up for the challenge.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

As fate would have it, my mother unexpectedly died prematurely from complications indirectly connected to Alzheimer’s, just a short time before we were scheduled to begin filming. I doubted whether I could go ahead but it would have meant canceling the production. I decided to begin filming as we had previously planned. Our cameras were rolling on Judith Anna Roberts in the role of Susan, a woman with Alzheimer’s, as she lay on a portable bed in the dining room of the house where only a short time ago my mother had slept. The settings were exactly the same, including the furniture and even the plastic bottles of pills. I never spoke to the cast or crew about how intense this was for me but everyone contributed to an atmosphere on the set that was conducive to my continuing to do the film.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

Fred Melamed plays a character loosely inspired by myself. He and I had been friends at college and for the decades since then at the time of casting. I had followed the great performances he had provided to directors such as Woody Allen and the Coen Brothers. He came to me the day before we began shooting and said, “Richard, if Elliott Gould is playing a character loosely based on your father——or inspired by your father——and I am playing a character based on or inspired by you, then your family is Jewish. This should be part of our improvisation.” I agreed with the analysis of my old friend.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

As I stayed nearby during the filming in a small cabin on the property of a home my brother owns, I began to reread one of my favorite books on Sigmund Freud, Freud and the Invention of Jewishness, written by the Brazilian Lacanian psychoanalyst Betty Fuks. The first time I read it, I had been struck by how illuminating I had found it about the work of Freud from a Lacanian perspective. In particular, I appreciated her emphasis on exile as a dimension of psychoanalysis that Freud develops out of his Jewish roots. Speaking of the importance of exile as a theme in Judaism, she cites the French writer Maurice Blanchot, from his book The Infinite Conversation:

“There is a truth of exile and there is a vocation of exile; and if being Jewish is being destined to dispersion—just as it is a call for staying without a place, just as it ruins every fixed relation of force with one individual, one group, or one state——it is because dispersion, faced with the exigency of the whole, also clears the way for a different exigency and finally forbids the temptation of Unity—Identity.”

Connecting this to the invention of psychoanalysis by Freud, Betty Fuks writes, “Psychoanalysis creates conditions in which subjects may come to experience what is foreign to them; Freud’s invention brings about a radical separation between the subject and the identical...This exile consists in making the subject seek——in the discomfort of repetition and in the gradual deconstruction of one’s own idolatry (narcissism of the ego and imperative of the superego)——what is most foreign to one: the confrontation with the unknown. To experience analytic exile is a learning of alterity: it allows the subject to search for a word to name what is both intimate and foreign.”

Fuks, Betty Bernando. Freud and the Invention of Jewishness. Translated by Paulo Henriques Britto, Agincourt Press, 2008.

It’s over a decade since we filmed in Katonah. Lately, in Athens, I have been reading again a famous essay by the Palestinian writer and intellectual Edward Said, entitled “Freud and the Non-European.” Its subject is Moses and Montheism, a late essay by Freud that is also crucial for Fuks. Said points to what he observes to be Freud’s “irremediably diasporic” and “unhoused” relation to his own Jewish heritage and sees in it a universal dimension. Said writes, “In our age of vast population transfers, of refugees, exiles, expatriates and immigrants, it can also be identified in the diasporic, wandering, unresolved, cosmopolitan consciousness of someone who is both inside and outside his community.”

For Fuks, Moses and Monotheism brings out a further dimension of exile intrinsic to Judaism that will provide an essential source of inspiration to Freud’s invention of psychoanalysis. Freud argues that Moses is Egyptian. At the heart of Jewish identity is a relation to the Other, writes Fuks. Said extends Freud’s postulation about the place of the Other at the origin of Jewish identity to include other people——including implicitly the Palestinians, for whose rights Said battled his entire life. He thereby can be said to be fulfilling a destiny for a key element of Judaism that inspired Freud's invention of psychoanalysis. As Jacqueline Rose, the well-known writer on psychoanalysis, Judaism and feminism, puts it in her postface to Said’s article, “...Freud believed——and some of the tensions described by Said can, I think, be traced to this belief——that it was the task of Jewish particularity to universalize itself.”

I have often thought that my father’s choice to not invite his parents to his wedding had to do with their being poor immigrants from a country in the South of Europe. However, reading in Athens the title of Said’s article, “Freud and the Non-European,” I am conscious that our family’s roots also contain a non-European origin. As Pontians, my paternal grandparents were diasporic Greeks fleeing in 1923 a genocide in Turkey being carried out by that country’s own form of extreme ethno-nationalism——for which it had found inspiration in Europe. For me, my paternal grandparents are Greeks, identified with the place sometimes known as the "cradle of Western Civilization,” but also, as Pontians, they are non-European. In Athens for a screening of my film Adieu Lacan at the Greek Film Archive, I began to wonder how much this had to do with my father’s choice not to invite them to his wedding. Some of the official documents my paternal grandparents carried as immigrants identified them as “Oriental.”

As I began to reflect on filming Fred Won’t Move Out after again rereading the book by Betty Fuks, exile started to appear to be at the heart of this film, in a different way for each of the characters. The nurse Victoria (Mfoniso Udofia) is a recent immigrant from Africa, working in a white household, separated from her husband and family in order to make a living and support them. Fred (Elliott Gould) and Susan (Judith Anna Roberts) both face in different ways exile from the home they made together and in which they raised their children; Susan additionally faces exile through her worsening loss of memory; Fred faces his own disabilities of aging and the loss of the control of his future that he has taken for granted as the family patriarch. Lila (Ariana Altman), their grandchild, is on the threshold of adulthood and leaving behind childhood. This is apparent in the film through her exploration of the spaces on the margins of the family space, such as the stonewall that marks its furthest boundary or the dark and cluttered barn. The daughter of Fred and Susan, Carol (Stephanie Roth Haberle), who drives up from the city with her brother Bob (Fred Melamed) and her daughter Lila, faces the loss of both of her parents. We see from the first greeting between Carol and her mother Susan a closeness and intimacy that is exceptional. At one point in the garden, which her mother has cared for since they first lived in the house, she begins to cry, comforted and witnessed only by her brother Bob. The music therapist——also named Bob——is going to be out of a job. He is representative of the new gig economy and has had taken from him the previous generation’s confidence to be able to rely on a wage that would support him raising a family. The son Bob has chosen filmmaking as a profession. Out for a walk, he runs into a childhood friend (played by myself). His childhood friend has chosen a more lucrative career in financial services. Bob is faced with exile from his assumptions of a heroic future of seeing his films on the big screen and must instead largely reconcile himself to the new world of streaming.

You may have noticed, I suspect, that I associate exile with a paradoxical loss. I think this is fair. For Lacan, our entry into speech marks a loss, which at best sets each of us on a journey, an Odyssey, from which there is no return—except fleetingly through our desire. Without this loss, we are lost in madness.

Thinking of all these different forms of exile, I am reminded of how Lacan reinterpreted Freud’s famous statement, wo es war, soll ich verden, “where it was, I will be.” Ego-psychologists had interpreted this to mean that the ego must come to dominate where the nomadic id——representing the unconscious——once roamed. Lacan, on the other hand, takes a different route, interpreting the “I” of the statement to be the subject who emerges through speaking and who must accept her exile from any fixed identity, and come to accept her nomadic relation to unconscious desire.

Still image from Fred Won’t Move Out

As I operated the second camera and Valentina Caniglia operated the first camera, the family created by the actors gathered around the character inspired by my then recently deceased mother. When together they began to sing familiar show tunes, I was overcome with gratitude for my family, for the work I was doing and for those working with me.