The Greeks of V13

Asked after the screening of V13, what I thought Freud would have wanted to talk about, I started my answer by saying simply, “Gaza.”

While attending, as a day-student, a private boys’ school in Katonah, New York, at the age of thirteen in 1969, I remember very clearly being shown Night and Fog by Alain Resnais. The Holocaust and the Civil Rights Movement became the foundation in my mind of what formed an ethical citizenship in the United States, with the pursuit of equality of all its people under the law being its guiding principle. It occurs to me now that both of these came with an indelible iconography of what could happen if these struggles were abandoned or replaced with hatred.

Nuit et Brouillard, Dir. Alain Resnais, 1956

In my late 20s, returning from Europe after around seven years, I felt very lucky when I was given an opportunity to write regularly on video, film and performance art for the magazine Artforum. I had been doing this for over a year when I proposed I write about a curated group of videos playing in the basement of Artists Space. It was a collection of videos made by Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank, entitled Uprising: Videotapes on the Palestinian Resistance. It was organized by Elia Suleiman and Dan Walworth. My editor accepted my proposal but when I turned in the review he said it made no sense. I rewrote it. I got the same response. I had absolutely no doubt at that point that I had crossed an invisible line, that I wasn’t supposed to review a collection of videos made by Palestinians. I was completely thunderstruck. I tried another art magazine that was publishing my reviews and received an even more hostile response. I felt that, without making it explicit, they were asking me to be complicit in a racist denial of representation that broke with my primary ethical imperatives but that otherwise I might risk being called an antisemite. I asked a friend whose opinion I respected about what I should do. He said the choice was mine but that if I pursued what might lead to an allegation by me that Artforum was biased against Palestinians, it would likely change my life and necessarily become a major focus of it. I walked away from the fight. I was conflicted about this choice but I didn’t pursue it further. A month later they told me that I was no longer needed to write small reviews in the back of each issue.

Palestine, Gaza, Jabalia refugee camp destroyed, photo: Omar Al-Qattaa

It took me over ten years to make the film V13, my film based on the play Vienne 1913 by French Lacanian psychoanalyst and my friend Alain Didier-Weill. It might never have happened if Alan Cumming hadn’t agreed to play Sigmund Freud and stuck with the project for many years. I always knew that making V13 would make me face the silence in which I had been complicit but I had confidence that through working with the play of Alain Didier-Weill, with its exploration of Freud, psychoanalysis and the rise of the Nazi Weltanschauung, it would allow me somehow to return to this same set of issues and this time not walk away.

I miss Alain, who died in 2017. I always enjoyed spending time together with him, either one-on-one–I remember countless times we met at the cafe Le Select–or with our friends and members of our families. I made two feature films based on his writings, The Caller (2008), which won a prize at the Tribeca Film Festival for Best Made in NY Film, and V13. The development of these two film projects provided the basis for a friendship I was fortunate to share with Alain for over twenty years, up until his untimely death in 2017. I never thought of what we did together as work but I was always working with Alain’s writings.

One of Alain’s most Quixotic choices in Vienne 1913 was to create for Hitler a prehistory of hating the ancient Greeks before hating the Jews. The young man who is known only as Adolf at the beginning of the film at the end of V13 announces his full name, Adolf Hitler. In his final meeting with Molly, a young woman working in the men’s shelter where he has been living, Adolf explains to her the Viennese origins of his particular brand of hatred for Jews. We can see how this hatred has become the solution to both his personal and political problems. At the beginning of the film, it’s the Greeks–meaning the ancient Greeks–that he hates. As far as I can discover through research, Adolf’s passage through a period of hating obsessively and with singular intensity the ancient Greeks is completely a creation of Alain’s. In Mein Kampf, Hitler speaks of the Romans, the Greeks and the Aryans as sharing common genetic roots. Many ethno-nationalist movements which had their beginnings in Europe at the end of the 19th century thought of Ancient Greece and their own nation in similar ways. The whiteness of Greek statues was read as proof of the concept of a white European race. It’s no small thing for Alain to have completely invented for Adolf’s youth the hatred for a particular people and their culture. Racism against modern Greeks has been a regular feature of European culture, even very recently, but not ancient Greece. Alain’s conception of the Greeks as the object of Adolf’s hatred, I would argue, is derived from Greeks such as we find their culture portrayed in the writings of Freud and not as ancient Greece was recruited into the mythical histories of European ethno-national movements at the end of the 19th century. Freud’s thinking about the ancient Greeks is focused on Greek tragedies composed in Athens. These works of poetry address profoundly alterity as an ineluctable part of each person and of society–what the French philosopher Jacques Derrida referred to in ancient Greek culture as “the irruption of the other.”

I propose that for Freud there was a confluence between, on the one hand, his experience of growing up in his Jewish home and his understanding of Jewish culture–as Betty Fuks illustrates in her book Freud and the Invention of Jewishness–and, on the other hand, ancient Greece, in particular, the experience of reading Greek tragedy. Both cultures give a fundamental importance to the role of the stranger, to exile and to alterity. This is not to say that for Freud these two are identical but that for him this shared aspect of these two traditions was generative of an aspiration to universality that is despised by Adolf in V13. Alain shows us different formulations of universality—including Christianity, Marxism and psychoanalysis—being transformed and transmitted through encounters with both of them.

Freud’s conception of Greece, therefore, differs radically from the Hellenism imagined by ethno-nationalist movements and eugenicists and adopted by these movements at the end of the 19th century–including by Zionism. Alain never mentions Zionism in Vienne 1913, although it was another nationalist movement, of particular relevance, emerging at this same time in Vienna. I propose that this silence on the part of V13 while the film highlights a fictional hatred of Hitler for the Greeks can fruitfully be read together.

Freud’s last monumental work, Moses and Monotheism, which argues in favor of the hypothesis that Moses is Egyptian–an Arab–completely undermines the model of racial purity that Zionism shared with other ethno-nationalist movements in Europe. These movements projected onto the imperialism of ancient Periclean Athens the new 19th century biomedical discourses of race and eugenics that accompanied colonialism. The reception of these concepts that originated in Europe was not limited to Europe. They were enthusiastically embraced elsewhere. They were present in Jim Crow and immigration laws in the United States where they were championed by its own nativist movement. This is where I chose to film V13, taking present day New York for Vienna in 1913. In Turkey, the Turkish nationalist movement known as the Young Turks, inspired by European nationalist movements of this same period, carried out the genocide of the Armenians with the aim of creating an ethno-nationalist state. The genocide of the Armenians also subsequently included the genocide of other Christian Orthodox communities in Turkey, including the Greek Orthodox, to which my paternal grandparents belonged until they fled to the United States in 1922.

Last year, in the winter of 2024, I was in Athens to attend a screening of my film Adieu Lacan at the Greek Film Archive. I was re-reading at this time the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said’s seminal essay “Freud and the Non-European,” which he wrote about Moses and Monotheism and which is now published with a postscript by the scholar of psychoanalysis Jacqueline Rose. A Greek online publication asked me to write on what it felt like to be a filmmaker of Greek descent returning to screen a film in the homeland of his paternal grandparents. This request and reading Said’s essay drove home for me that my Greek ancestors had never lived within the national borders of Greece, even if the Pontian Greeks have lived in communities around the Black Sea since the 8th century BCE. I began to think of the important and irreducible role of estrangement in my affiliation to Greece.

Jacqueline Rose, in an essay published in the New York Review of Books in 2004, with the title In Our Present-Day White Christian Culture, and with the subtitle, Jacqueline Rose on Freud and the Rise of Zionism, writes,

Watching the rise of Jewish persecution and Zionism together, Freud was well placed to ask the question that has returned to us so brutally since 9/11: how do you save a people at one and the same time from hatred of others and from itself?

Freud’s last great work – Moses the Man and Monotheistic Religion (I take the title from Underwood’s new translation) – is his final, urgent attempt to address this question. He makes Moses an Egyptian, thereby ‘robbing’ his people of their ‘greatest son’. Arguing that the monotheistic religion was founded not once but twice, by two disparate peoples brought together through the upheavals of their history, he sows dissension in the tribe. He does not want his people unified. Or, if he does, he wants them unified differently: not created once in an act of divinely sanctioned triumphant recognition, which henceforth will brook no argument, but torn internally by a complex, multiple past. He wants, as Edward Said stressed, a group that might be capable of imagining itself as founded by a stranger.

The Hellenism manufactured in Europe in the 19th century was an imaginary past according to which there was once a pure white race completely segregated from others, defined as biologically determined races. “In Greece,” writes Theodor Herzyl, the founder of modern political Zionism, “we are at the world’s cradle.” This fantasy about Greece arguably has recently resurfaced in a speech of Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in which he proposed that Israel now needs to become a “Super Sparta.” I am drawing a radical distinction between this vision of ancient Greece that Theodor Herzl would evoke and the one that inspired Freud, and which is defined by its unstable and unresolved relation to alterity, the other.

In their essay Of Europe: Zionism and the Jewish Other in the book Europe After Derrida, Sherene Seikaly and Max Ajl state that what distinguishes Zionism from the other ethno-nationalist movements of the same period is that its project evolves into creating outside of Europe a state elsewhere that wants to separate itself from Europe and in doing so become European. I recognize that I am leaving aside several other ideas of what Zionism could be, but I am speaking of Zionism from the perspective of today, when Israel has clearly become a state employing an ideology of racial superiority and having carried out a genocide against the Palestinians that makes clear that Israel considers them an inferior colonized race.

Zionism–again according to Seikaly and Ajl–at its beginnings proposed two imaginary acts of purification at the same time: the first was to abstract the Jewish people from Europe, where they had been regularly treated as scapegoats and seen as a contamination, culminating in the Holocaust, and, for the second act of purification, to rid themselves of so-called Oriental contaminations. The second act of purification was proposed as necessary by Zionists like Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau, co-founder of political Zionism, physician and notably the author of the book, Degeneration, so that the new state could give birth elsewhere to what were seen as European values. Orientalism–which, by the way, is a racial category into which my paternal grandparents would have been placed–is accused of being the cause, according to Nordau, that Jewish men tend to be too intellectual and therefore too feminine, which he wants to replace with a “muscular Judaism.” Seikaly and Ajl write, for Theodor Herzl, ‘the Jews of the medieval ghetto in Germany were an “Oriental tribe”...they wore “Oriental costume”; their speech was “Oriental”’ (Kornberg 1993:24). It was this orient that had to be purified and erased.

If we want to capture in a single image the contrast between the Zionist approach of this period and Freud's approach to this other who comes from the East, we can start by looking at Freud's couch covered by Persian rugs. Freud himself spoke of it using the German word die Couch or das Ruhebett but in private correspondence would sometimes use the French derived from the Persian word, divan. Ernest Jones, in his biography of Freud, refers to “Freud’s famous Oriental divan.” With Freud, I propose, one Orientalizes or one Westernizes from the East, one speaks with and is spoken by the other within; in a formulation indebted to Derrida, we can say that to be Western, one finds oneself elsewhere and looks toward the West. This is a relationship to the other for which we can find a precedent in Greek tragedy and with which Freud found an affinity with the importance of the other in Judaism.

The standard English Edition translated by James Strachey of Freud’s collected works extends to twenty-three volumes. In the very last printed article, preceding the index, he recounts being asked to write about antisemitism but declines to do so, instead writing that he would prefer if someone who is not Jewish write about it. This can be interpreted many ways. I read it as eliciting the international solidarity that would soon prove to be absent during the Holocaust. As someone who is not Palestinian I hear Freud’s statement as eliciting today solidarity with the Palestinians when the United States and Germany are the two largest suppliers of arms to Israel in its carrying out of a genocide, starvation and ethnic cleansing against them. Freud’s choice not to speak can also be seen as a way of avoiding the reduction of the human subject to identity. In the world at that time, during the Second World War, there were everywhere around Freud forms of ethno-nationalism and ideas of eugenics that take as given a reductive conception of identity. Of course, this could be found among the Nazis, but also among the Americans, the English, and also among the Zionists. In this context, his essay Moses and Monotheism can be read as a direct challenge to the eugenic conception that Zionism shared at that time with the other ethno-nationalist movements that surrounded Freud.

If Freud wanted, as I would argue Alain Didier-Weill proposes in Vienne 1913, to universalize a dimension of Judaism through psychoanalysis, then it was necessary to establish the other—that is, non-identity—at the heart of Judaism and implicitly reject the idea of race that is fundamental to Zionism in the same way as it is to other ethno-nationalist movements of this period. V13's fiction regarding the Greeks—substituting Freud's Greeks for the Greeks of Zionism—is a way of simultaneously naming and displacing the truth of the distance between Freud's Judaism and Zionism.

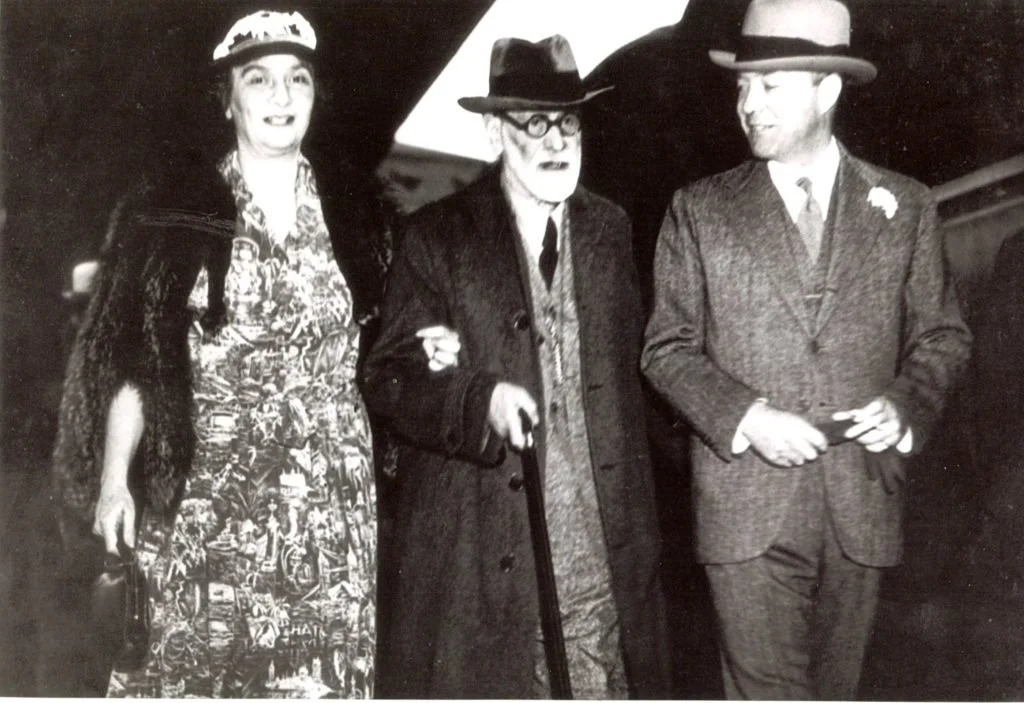

Sigmund Freud in London

As you know, the Freud Museum in London today is the house where Freud lived with his wife Martha and their daughter Anna after fleeing the Nazis in Vienna, and where he died in 1939. Earlier this year, 2025, I was invited to screen V13 at this house and, after the screening, to be interviewed by the English Lacanian psychoanalyst Janet Haney. While the film was playing, I waited in what had been the cabinet of Anna Freud. I reflected on what it must have been like for her father Sigmund Freud not only to escape Vienna at the age of 82 but to have undertaken the enormous effort to restart his work in London. It was here at the Freud Museum in London that Edward Said gave his lecture Freud and the Non-European, after having been given and later had withdrawn an invitation to give a lecture at the Freud Institute in Vienna. Asked after the screening of V13, what I thought Freud would have wanted to talk about, I started my answer by saying simply, “Gaza.”

Before the screening, while the museum was closed, I was given permission to wander through Freud's study beyond the regular visitor limits. I took a photo of the small statue of Athena that Freud always claimed was his favorite of the small statues of gods and religious figurines that he collected. Several works of art brought by Freud from Vienna changed locations in his new exile residence, but this small statue remained in the same place, at the center of the desk. Our host, during our visit, the caretaker of the house whose father had been the caretaker of the house for Anna Freud, informed me that Freud died in a bed he had asked to be placed in front of his desk. From here, I noted, he could see his collection of statues, principally Athena.

It is the dimension of non-identity that he found in his reading of Judaism and Greek tragedy. This link between Judaism and the other—as Betty Fuks and Edward Said have pointed out in different ways, in their readings of Moses and Monotheism—is the reason why, in my opinion, Freud not only took to London a small statue of Athena, his favorite sculpture, but also gave it the same position: the unconscious for which he draws inspiration both from Jewish Scripture and Greek Tragedy.

Alain’s fiction of Hitler hating the Greeks of Freud rather than loving the Greeks of European ethno-nationalist movements was certainly one important element of Vienne 1913 that drew me to making V13.

Works Cited

Didier-Weill, Alain. Vienne 1913. Aubier, 1991.

Freud, Sigmund. Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays. Translated by Katherine Jones, edited by James Strachey. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 23, Hogarth Press, 1964, pp. 1–137.

— “Anti-Semitism in England.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 23, London: Hogarth Press / Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1964, pp. 291–303.

Fuks, Betty Bernardo. Freud and the Invention of Jewishness. Translated by Paulo Henriques Britto, Agincourt Press, 2008.

Jones, Ernest. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. 3 vols., Hogarth Press, 1953–1957.

Ledes, Richard, director. Adieu Lacan. 2021.

— director. V13. 2022.

Nordau, Max. Dégénération. Félix Alcan, 1892.

Resnais, Alain, director. Night and Fog (Nuit et Brouillard). 1956.

Rose, Jacqueline. “In Our Present-Day White Christian Culture: Freud and the Rise of Zionism.” London Review of Books, vol. 26, no. 13, 8 July 2004, p. 14.

Said, Edward W. Freud and the Non-European. Verso, 2003.

Seikaly, Sherene, and Max Ajl. “Of Europe: Zionism and the Jewish Other.” Europe after Derrida: Crisis and Potentiality, edited by Agnes Czajka and Bora Isyar, Edinburgh University Press, 2013, pp. 120–133.

https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/145834-gaza-darfur-genocide-convention.html